Interview: 'It was the nearest I’ve come to hell' - war hero's emotional memories leave Harborough family in awe

Lt Robin Rowland was leading his vital 100-strong army mule train through war-torn India in May 1944 when he heard the sweet sounds of music in the distance.

Already knee deep into the Second World War, the intrigued British officer briefly paused from fighting the Japanese to hastily stroll across the scrubland and have a closer look.

Advertisement

Advertisement

And there Robin, just 22 at the time, spotted the one and only Vera Lynn belting out hit after glorious hit to thousands of spellbound British and Empire troops.

“I could hardly believe it!

“There was Vera Lynn, the nation’s sweetheart, singing the likes of We’ll Meet Again and the White Cliffs of Dover at the top of her voice just 200-300 yards from me and my mules,” said Robin, who now lives in a village near Market Harborough.

“She had all of these battle-hardened soldiers eating out of her hand in the middle of nowhere.

“It was just such an amazing moment, so utterly surreal.

“I watched Vera and listened to her for about 15 minutes before I had to push off and get back on with the war.

“It was all so civilised, so friendly.

Advertisement

Advertisement

“And it was such a dramatic contrast to the evil that many of us had experienced fighting Japanese forces.”

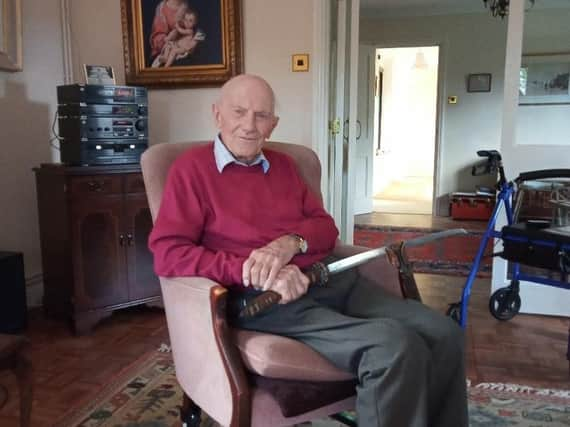

Now an astonishingly sprightly 98, Robin said those magical immortal 15 minutes have lived with him for over 76 years since.

“I can still remember listening to Vera as if it was yesterday.

“She put on such a wonderful performance.

“There’s no doubt at all about the tremendous effect she had on the morale of our lads,” said the extraordinary British Indian Army veteran.

“It was just incredible – and I’ll never forget it.

Advertisement

Advertisement

“Vera certainly put a smile on my young face and a new spring in my step!”

The priceless cameo emerged as Robin spoke to me for over three hours at his home in South Luffenham about his action-packed service in the fabled 14th Army – the iconic Forgotten Army.

The young officer battled the all-conquering Japanese in the most brutal British theatre of war for three tough years.

And it is especially poignant that we tell his powerful story now hard on the heels of marking the 75th anniversary of Japan’s surrender, VJ Day, on August 15.

Advertisement

Advertisement

Born in Co Antrim, Northern Ireland, in January 1922, Robin, the son of a top professional soldier, went to Belfast’s Queen’s University to study law when he was 18.

“I decided that I wanted to pursue a career in law.

“But then the Second World War broke out in September 1939 and changed everything,” he said as his youngest son Andrew, 63, of Kibworth Beauchamp, sat with us listening intently.

“I joined the Officer Training Corps at Queen’s.

“There was no conscription in Northern Ireland for political reasons.

“But I decided I wanted to serve my country and I volunteered to join the army in 1941.

Advertisement

Advertisement

“I received a telegram on December 13, 1941 – just six days after the Japanese attack on the US naval base at Pearl Harbor – to sail to India.

“We sailed from Greenock on the Clyde on the Strathnaver in convoy to Bombay with about 4,000 other troops on board.

“We landed on March 8, 1942.

“I then went straight to the officer cadet training school in Mhow in central India.

“The training was intense, exhausting, with temperatures topping 100F at times and the monsoon soaking us all from May to September,” said Robin, whose razor-sharp memory and instant power of recall would be remarkable for a man of 38 never mind 98.

Advertisement

Advertisement

“I was commissioned in July 1942 and posted to the Royal Deccan Horse as a second lieutenant.

“I served with the unit for about six months before being posted to the 7th Battalion of the 2nd Punjab Regiment – and ended up commanding B Company down the line.

“We all knew that we were taking part in something epic.

“We were fighting for our very survival as a nation.

“Japanese forces had taken Malaya, Hong Kong, the Dutch East Indies, Borneo and Burma.

“They had conquered a huge slice of the British Empire.

“Losing Singapore in particular had come as a great shock to all of us.

Advertisement

Advertisement

“There wasn’t much fighting – the Japanese just seemed to walk in.

“We knew we had to confront and fight the Japanese head on to get all our lost territories back.

“I spent a lot of 1943 doing more intensive training in Ranchi in eastern India as Bill Slim, our brilliant commanding officer, prepared to lead us back into Burma.

“General Slim convinced us that the Japanese were not supermen and could be beaten.

Advertisement

Advertisement

“I worked with mortar platoons and Bren gun carriers as I got used to taking charge of men and winning their trust and support.

“I excelled at it.

“We trained with live ammo some of the time and as I assumed greater responsibility I vowed that I’d never ask my men to do something that I wouldn’t do.

“I got on really well with my Indian troops but some had served for 20 years and I had to earn their respect.

“I also had to learn their language, Urdu, fluently because they didn’t speak English.

“I can still speak it to this day.

Advertisement

Advertisement

“We trained with the 7th Indian Division in a mix of jungle and dry terrain in Ranchi.

“I first went into action in September 1943 in the Arakan campaign,” said Robin, who wrote an introduction to his good soldier friend John Shipster’s acclaimed campaign book ‘Mist on the Rice-Fields’.

“We were part of a big force detailed to recover Burma.

“We were fighting in thick bamboo jungle – it was a very unreal type of warfare.

“I led out a patrol to recover the wounded after a reconnaissance unit ran into trouble and suffered casualties.

Advertisement

Advertisement

“I took out 40 men on to a narrow path with the moon shining down at night.

“The Japanese were still out there in the scrub jungle.

“But we never knew where they were, they were so adept at hiding from us, so there was a constant threat of deadly ambush.

“We made it back all right but had to lie up outside our battalion HQ in case we were shot by our own side!

“I was too busy to be scared, I just tried to concentrate on my job.

Advertisement

Advertisement

“But none of us wanted to be taken prisoner by Japanese soldiers.

“We’d all heard too much about their cruelty – including a captured officer being tied to a tree and bayoneted to death.

“They treated our PoWs very badly.

“On February 4, 1944 we were mortared and shelled at our camp in what became known as the Battle of the Admin Box.

“The Japanese threw everything at us and we came under terrific bombardment.

“We were well dug in in slit trenches and bunkers.

Advertisement

Advertisement

“And the Japanese hadn’t done their homework as we were brilliantly supplied from the air by a fleet of Dakotas.

“The battle went on for seven weeks before the Japanese gave up.

“Half of the 7,000 Japanese servicemen involved were killed or injured.

“We were manning excellent defensive positions and I can still see fired-up Japanese troops running at us, screaming and shooting.

Advertisement

Advertisement

“It was a great honour for the Japanese soldier to die fighting for the emperor – they were a very fierce foe.

“But we knew we had the measure of them after the Admin Box.”

The stakes got even higher for shattered Robin and his comrades as they were plunged into the bloody pivotal battle of Kohima, the capital of Nagaland in north-east India.

“We heard we were in big trouble there and we were moved at the start of May 1944.

Advertisement

Advertisement

“We travelled about 200 miles to the north by rail, river and road after losing eight officers, about half of our entire establishment, in the Arakan.

“I was ordered to ferry a mule train of crucial supplies such as ammo, food and water to our besieged men at Kohima.

“And that’s when I came across Vera Lynn singing her heart out!

“I left Dimapur, about 45 miles away, and set off for Kohima with Vera still ringing in my ears.

Advertisement

Advertisement

“Kohima was a large village in thick jungle sitting about 5,000 feet above sea level.

“Japan was determined to annex India, she was the big prize, and they marched on Imphal and Kohima – the gateway to northern India,” recalled Robin, his memory still crystal clear.

“I got there as the Japanese were attacking us in great force.

“Their shells cut trees in half and wreaked total devastation as I could smell the stench of decomposing human flesh.

“It was the nearest I’ve come to hell.

Advertisement

Advertisement

“We were set up on Treasury Hill as we occupied a defensive position to stop Japanese counter-attacks.

“The Japanese planned to take Kohima in three or four days, kill all the defenders and storm into India.

“But we stopped them point blank in their tracks.

“And the battle of Kohima became one of the British Army’s greatest ever victories.

“The Indian monsoon was at its height and we set out to march 900 miles.

“It was so wet the mud was up to our knees.

“We smelled more death in the dense teak jungle.

Advertisement

Advertisement

“Starving Japanese troops were piled up by the trail after collapsing and dying as they retreated from the hell of Kohima.

“I’ll never forget the sight of dead enemy soldiers half eaten by wild animals.

“But the Japanese were truly on the run, they were a broken army – and they never won again in Burma,” said Robin, who starred in the BBC’s coverage of VJ Day.

“We regrouped and rebuilt the rest of 1944 before going down to the Mandalay plain in early 1945.

“I had now been promoted to Major after Kohima.

Advertisement

Advertisement

“I was ordered to reconnoitre Japanese positions and occupied the high ground at Point 1186, some 25 miles south of the mighty Irrawaddy river.

“We were attacked and shelled for three nights running as the Japanese mounted a desperate rearguard action.

“Bill Slim pulled off his masterstroke feint crossing of the Irrawaddy and our morale was sky high as enemy forces went into full retreat.

“We were in Pegu in central Burma in August 1945 when America carried out the twin atomic bomb attacks on Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

Advertisement

Advertisement

“There’s been a lot of discussion since about the rights and wrongs of dropping the A-bombs and killing so many people.

“But for us out there fighting at the time the morality of dropping those bombs was never a problem because our lives had been saved.

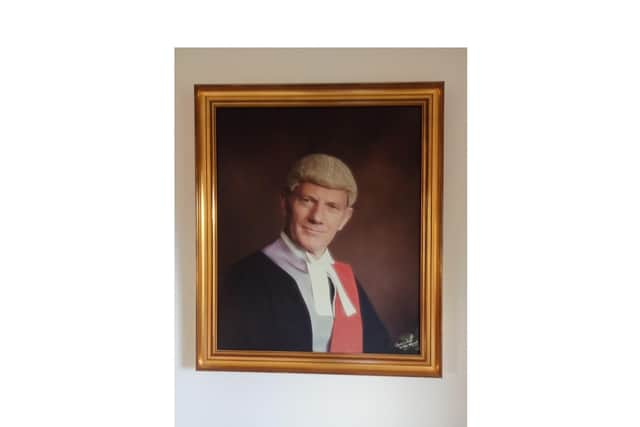

“And it would have cost hundreds of thousands of Allied soldiers’ lives if we had been forced to invade Japan,” insisted Robin, who went on to become a top barrister and county court judge in Northern Ireland after the war.

“I was sent to disarm the Japanese 22nd Division in Ubon on the Mekong River in Siam, now Thailand.

Advertisement

Advertisement

“We seized all their weapons, including their ceremonial swords – which seriously hurt their pride.

“I still have the beautiful sword I took off a sergeant major.

“The war was over and I was alive.

“I left County Antrim as a boy – and I returned a very experienced man.”

Robin met Kay, the sweetheart of his life, while she was serving as a Queen Alexandra nurse in Malaysian capital Kuala Lumpur.

“I knew she was the one for me the first time I met her.

Advertisement

Advertisement

“We used to dance at the famous Lake Club every weekend and got on so well,” said Robin, who moved to South Luffenham 23 years ago and was a passionate fly fisherman.

“We got married in London on August 14, 1952.

“My oldest son Peter was born in July 1953 – and he’s now settled out in Adelaide – before Andrew came along in 1956.

“We had a long and happy marriage before Kay sadly died of cancer aged 70 on June 14, 1991.”

Asked if he regards himself as a hero, humble Robin, one of the last surviving Forgotten Army veterans anywhere in the world, replied: “No, I don’t think so.

Advertisement

Advertisement

“I was determined to serve from the first day the war broke out.

“It was the right thing to do and I’m pleased I did it.

“Serving our country out in India and Burma gave me terrific confidence.

“And that paid off in civil life after the war because I thought if I can come through this I can do anything,” said Robin, who didn’t get back to the UK until September 1946.

“But I can’t forgive the Japanese for what they did during the war – they were a terribly cruel enemy.”

Advertisement

Advertisement

His son Andrew, of Dover Street, Kibworth Beauchamp, told me as Robin looked on: “To say that I am incredibly proud of my father doesn’t do it justice.

“I and my brother are both in awe of him.

“My dad’s generation is often described as our greatest generation and that’s spot on.

“He has had an incredible life – one which we can never even imagine.

“And it becomes more and more critical to let our magnificent war veterans tell their unique stories so that we never forget before the last of these great men leaves us for ever.”