The life and death of a Harborough village railway station

The date is around 1900; the place is Hallaton; it’s one of 20 stations in villages within 15 miles of Market Harborough in the Golden Age of Railways.

Hallaton station has gone now; in fact all 20 village stations are abandoned.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

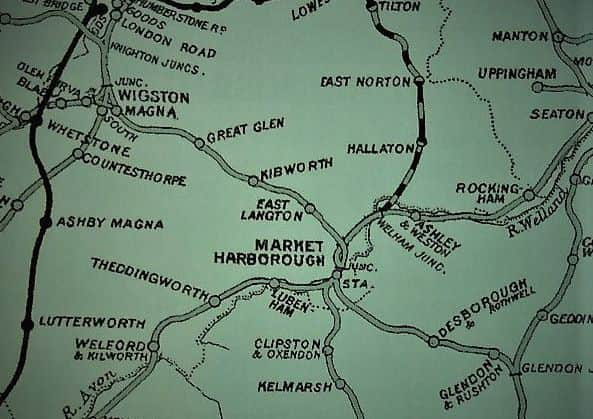

Hide AdBut as we heard last week, Market Harborough was once a railway hub, with six different lines going out across the Harborough countryside.

The last of these six lines was built by two railway companies – the London and North Western Railway and the Great Northern Railway.

It clattered south in stages from Newark and the Nottinghamshire coalfields, and created stations including Tilton, East Norton and Hallaton, before arriving in Market Harborough in 1879.

Despite being a village of only 750 people, Hallaton – like many other Harborough villages – was on the railway map.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdHallaton station had two waiting rooms, each with black leaded grates for fires in winter. The station was lit by 15 paraffin lamps, cleaned and re-filled daily.

The goods yard was spacious, with large goods sheds and livestock enclosures.

Typically, four platers worked out of Hallaton station, maintaining the local tracks. There was also a stationmaster, a porter signalman and a general porter.

Sid Reed, the junior porter at Hallaton in 1938 recalled his first job of the morning was to pump water for the station from a hand-pump in the nearby Railway Cottage gardens – there was no mains water. He also kept the station clean, sold tickets, supervised the weighing of trucks on the weighbridge and even loaded and unloaded livestock.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdYou could travel by train to anywhere in Britain from a village station like Hallaton. It had around five passenger trains a day to the Market Harborough hub (a nine minute journey); five more towards Melton and the north.

The trains would be used daily by villagers travelling to work and to school.

For many years, Hallaton children caught a morning train that would get them to the Grammar School in Market Harborough on time. They would then leave school early to catch the 4pm train home.

“Specials” through Hallaton took people to events – outbound in the summer to Skegness for example; into Hallaton on Easter Monday for the Bottle Kicking.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdBut goods were the mainstay of Hallaton station, from coal and cattle to post and papers. The double Grand National winner (1935 and 1936) Reynoldstown was transported by train from Hallaton.

“Put your shirt on him” the owner Major Noel Furlong advised the stationmaster. “And if you can find someone else’s shirt, put that on him too.”

Trains came through Hallaton at all hours of the day and night. A visitor to Railway Cottages recalls being woken regularly at night by the rattle of crockery in cupboards as another train trundled past.

But as road traffic increased, railways started to lose vast sums of money. The line including Hallaton station finally shut in 1957, aged 78, a victim of Dr Beeching’s cuts.

There’s a bungalow now where the station once stood.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdAnd interviewed in 2004, former Hallaton porter and Railway Cottages resident Sid Reed said: “The swallows that used to build their nests under the station eves still return every spring, but in fewer and fewer numbers.”

n Help and research by Pauline Ingham. Research by Phillip Baildon, John Morrison, Vic Mitchell, Keith Smith.