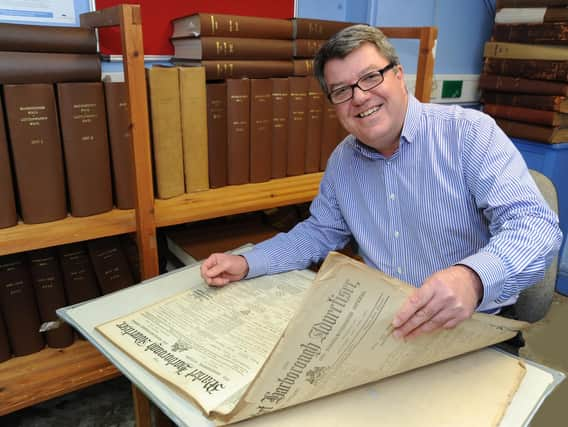

John's real-time WW1 blog: Swastika symbol used to help the British war effort

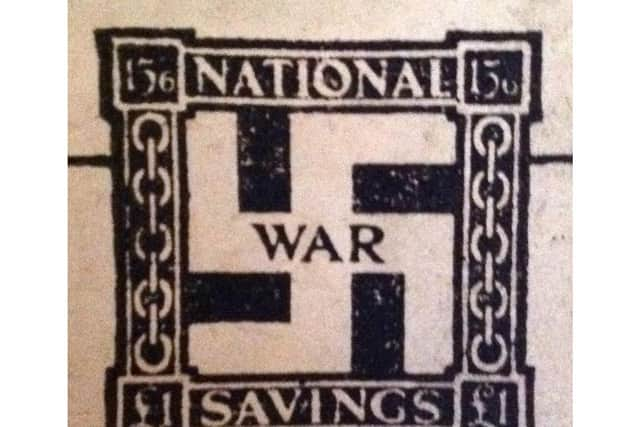

A swastika, pristine white on a starkly black background with the word WAR emblazoned in the centre, stares out of page 3 of the September 10, 1918, edition of the Market Harborough Advertiser.

To the 21st century reader we are tainted by the symbol’s evil association with Hitler’s Second World War Nazism and it is deeply disturbing to see it in a First World War newspaper. But in fact the swastika was a symbol of good fortune and had a history going back thousands of years in almost every culture in the world.

Advertisement

Advertisement

In the late 1800s and early 1900s the swastika was used in advertising and product design – even by big brands all over Europe and America.

In his book The Swastika: Symbol Beyond Redemption? US graphic design writer Steven Heller says: “Coca-Cola used it. Carlsberg used it on their beer bottles. The Boy Scouts adopted it and the Girls' Club of America called their magazine Swastika. They would even send out swastika badges to their young readers as a prize for selling copies of the magazine,” he says.

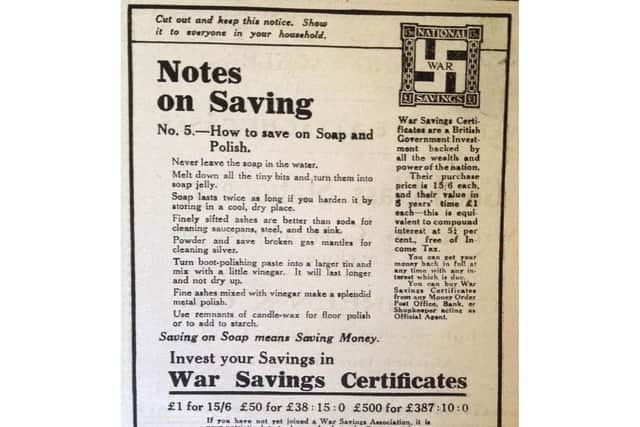

So in the context of 1918 it is not unsurprising to see the swastika being used as a badge of pride in an advert from the British Government urging readers to take out National War Savings.

The ad is also linked with notes on how Saving on Soap means Saving Money – and that allows the readers to invest in War Savings Certificates.

Advertisement

Advertisement

This week’s Advertiser is jam-packed with adverts of every sort with only a fraction of the space being left for editorial. There is only one tiny story – about Blaston – on the front page and no editorial on page 2. The other two pages of the normal Advertiser are also laden with classified and display adverts.

There is space, however, for news about one local lad who has paid the ultimate price for his country. 2nd Lieutenant Alan Grant of the Laurels, Kibworth was just 19 years old when he was injured and later died of his wounds.

Grant clearly came from a well-known family. The story says: “He was educated at Rugby School where he represented his house on both the cricket and football field and decided to enter the Army and went to Sandhurst where he came out eighth in a company of 200.”

His father is also well known. The story says: “Mr H T Grant who is, amongst other things, vice-chairman of both the Market Harborough Board if Guardians and Rural District Council.”

Advertisement

Advertisement

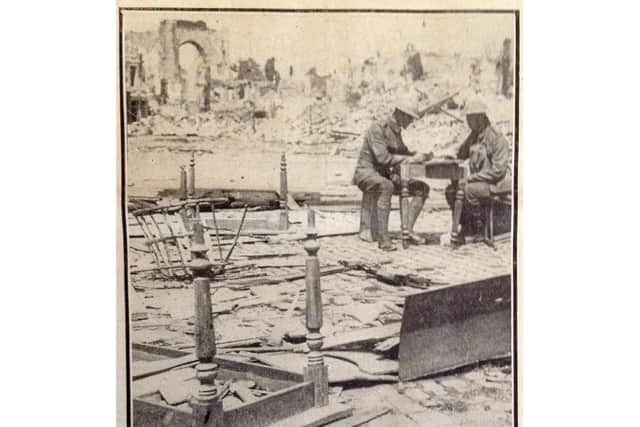

Readers looking for more editorial than the normal Advertiser provides are rewarded with the now regular inclusion of the Press Bureau-provided two-page War Supplement.

Among the selection of remarkable, officially taken photographs, is one which shows in mind-numbing clarity the devastation caused by war. Two British soldiers sit at a small table amidst what the caption calls a ‘desert region’.

The caption, attributed to a war correspondent, says: “When the name of a place is mentioned in all this desert region it merely means a position covered with ruins and rubble, without food, without water and without inhabitants.”

There is also a long story taken from The Times, where a reporter has interviewed an American dentist Dr Arthur N Davis, who for 14 years was ‘entrusted with the care of Kaiser’s teeth.

Advertisement

Advertisement

Davids left Germany a year ago before the United States joined the war and he has now written a book of his recollections’ – none of it very flattering about the German emperor as you can imagine.

Among the stories – which include the Kaiser’s delight at zeppelins murdering English women and children and his approval of the sinking of the Lusitania in 1915 – is a tale of how the Kaiser never had an anaesthetic.

David says: “At various times since the Kaiser had been my patient I had suggested that I could save him pain by the use of a local anaesthetic but he had always refused it. ‘The ladies like an anaesthetic, no doubt, Davis' he said, ‘but I can stand it without. Go ahead!’ and I may say, at this point, that in all my experience I never observed him to flinch while in the chair.”

This story, might, at first reading appear, as if this in casting the Kaiser in a good light. However, the story has a punchline: “Dr David has a shrewd comment. ‘It often occurred to me that in his own callousness to pain lay the secret of his disregard for the pain and suffering he cause in others.”

Advertisement

Advertisement

- This column is published every Monday by John Dilley on the Newspapers and the Great War website and will continue until the 100th anniversary of the final armistice in November 2018.

- My fellow researcher and De Montfort University lecturer David Penman is conducting a similar real-time project with the Ashbourne Telegraph. Check out his Great War Reports.

- Check out this week’s Harborough Mail for current news from the Market Harborough area.